I’m a sucker for TV books, even those about shows I didn’t watch or don’t particularly like…because, often, I can learn something new about the development, writing and production of TV series that I didn’t know before despite my own experience in the biz. Here are some short reviews of three recent releases.

I’m a sucker for TV books, even those about shows I didn’t watch or don’t particularly like…because, often, I can learn something new about the development, writing and production of TV series that I didn’t know before despite my own experience in the biz. Here are some short reviews of three recent releases.

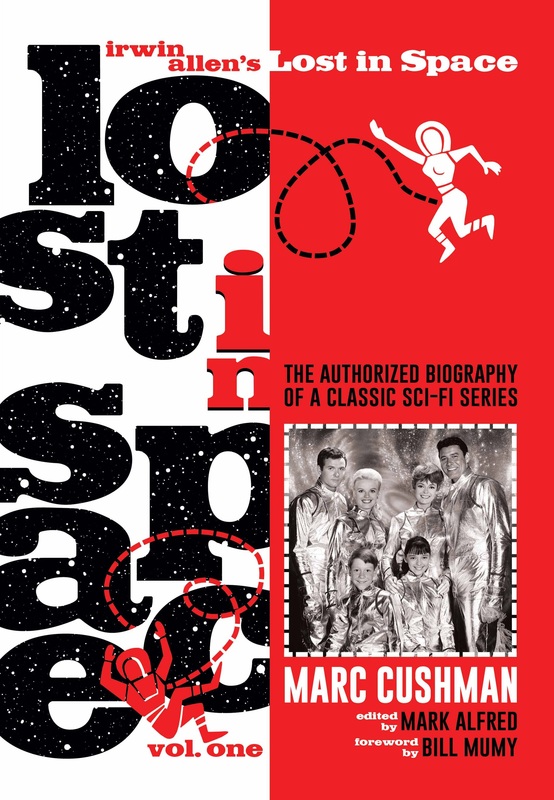

Irwin Allen’s Lost In Space: The Authorized Biography of a Classic Sci-Fi Series Vol. One by Marc Cushman. Jacobs-Brown Publishers. This is a monumental work of TV history…one of the best TV reference books ever written. That’s no surprise, since it’s from the same people who did These Are the Voyages, the three volume, definitive work about the TV series Star Trek and that is also a stunning achievement. I didn’t think that series of books could be topped or even matched. I was wrong. This nearly 700 page paperback covers the first season of Lost in Space, and as a bonus, the development of Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea, the Irwin Allen series that preceded this one.

I am not a fan of Lost in Space, but that didn’t limit my enjoyment or appreciation of this book one bit (though I have to admit I haven’t finished it). The book is a remarkable achievement that exhaustively covers every detail of the creation, writing and production of the show, relying on interviews, memos, scripts, letter, photos… the amount of material they uncovered and examined is incredible and, at times, overwhelming. And yet, it doesn’t feel like overkill and it’s never dull. The author has an engaging style that rises above similar books.

Each episode is examined in-depth, from idea, through all stages of production, right down to the ratings and critical reaction to the final airing. What makes this book even more special is that, unlike Star Trek, the authors aren’t following a well-trodden path…so much of this is new and fascinating information. Yes, this show has been examined before, in documentaries and articles, but never in such detail and, surprisingly, with such objectivity. The authors aren’t slavishly devoted fans… they don’t hesistate to point out how awful some of the episodes were.

This book is a must-stock for any library and a must-read for anyone interested in the business behind the TV business. You don’t have to be a fan of Lost in Space, or have ever watched a single episode, to benefit from this great book. I can’t wait for the volumes 2 & 3.

Cop Shows: A Critical History of Police Dramas on Television by Roger Sabin & others. McFarland & Co. I had high hopes for this book because I’m a huge fan of cop shows. I was expecting to glean some new insights into familiar and obscure shows, and new details about how these shows were made, the impact they had on culture, etc. What I got instead was a very scholarly, very broad series of superficial essays about individual shows that revealed nothing new…besides the authors’ opinions, which I don’t really care about. I was also dismayed by the sloppy errors, which made me wonder if they actually watched the shows they were writing about…or were simply lazy in their research. For instance, in their chapter on Hawaii Five-O, they make a passing reference to Stephen J Cannell’s unsold reboot pilot, which was shot but never aired. They say that Gary Busey starred as McGarrett. In fact, nobody played McGarrett in the pilot…and Busey was co-lead with Russell Wong. This information is easily found on the Internet and in other reference books. Later, in their short summary on TJ Hooker, they say “CBS picked up the show’s final season, which was a marked by grittier plotlines and a location shift to Chicago. .. the changes proved deeply unpopular with fans.” That is absolutely wrong. The final episode of the ABC season was set in Chicago, and was a pilot for a potential reboot, but when the show moved to CBS, they kept the original concept, setting, and storylines (going so far as to only use car chases from previous episodes instead of shooting new ones!). The only thing that changed was that Adrian Zmed was dropped from the cast. So not only are they factually wrong, but the conclusions they came to about “grittier storylines” and the audience dissatisfaction with them is total fiction. If that is an example of their academic rigor, I grade this thesis a C-.

Cop Shows: A Critical History of Police Dramas on Television by Roger Sabin & others. McFarland & Co. I had high hopes for this book because I’m a huge fan of cop shows. I was expecting to glean some new insights into familiar and obscure shows, and new details about how these shows were made, the impact they had on culture, etc. What I got instead was a very scholarly, very broad series of superficial essays about individual shows that revealed nothing new…besides the authors’ opinions, which I don’t really care about. I was also dismayed by the sloppy errors, which made me wonder if they actually watched the shows they were writing about…or were simply lazy in their research. For instance, in their chapter on Hawaii Five-O, they make a passing reference to Stephen J Cannell’s unsold reboot pilot, which was shot but never aired. They say that Gary Busey starred as McGarrett. In fact, nobody played McGarrett in the pilot…and Busey was co-lead with Russell Wong. This information is easily found on the Internet and in other reference books. Later, in their short summary on TJ Hooker, they say “CBS picked up the show’s final season, which was a marked by grittier plotlines and a location shift to Chicago. .. the changes proved deeply unpopular with fans.” That is absolutely wrong. The final episode of the ABC season was set in Chicago, and was a pilot for a potential reboot, but when the show moved to CBS, they kept the original concept, setting, and storylines (going so far as to only use car chases from previous episodes instead of shooting new ones!). The only thing that changed was that Adrian Zmed was dropped from the cast. So not only are they factually wrong, but the conclusions they came to about “grittier storylines” and the audience dissatisfaction with them is total fiction. If that is an example of their academic rigor, I grade this thesis a C-.

Seinfeldia: How a Show about Nothing Changed Everything. by Jennifer Keishan Armstrong. Simon and Schuster. I totally get why this book has become an unlikely bestseller. For one thing, it’s about one of the most popular and beloved sitcoms in TV history. But most of all, it’s because the book is so readable…so entertaining…that it almost feels more like a novel about a show than a book about TV history. Even so, there’s lots of meat here for people interested in how the TV business works, how a TV series develops and evolves, and, most of all, how a series is written. What this book is really about is the writing of a TV series and, as a writer myself, I found it irresistible and fascinating. There have been other books written about Seinfeld…but none of them are as good, or as useful, or as educational as this one. You should also grab Mary and Lou and Rhoda and Ted, her terrific book about The Mary Tyler Moore Show.

If you’ve read my novel

If you’ve read my novel

I’m a sucker for TV books, even those about shows I didn’t watch or don’t particularly like…because, often, I can learn something new about the development, writing and production of TV series that I didn’t know before despite my own experience in the biz. Here are some short reviews of three recent releases.

I’m a sucker for TV books, even those about shows I didn’t watch or don’t particularly like…because, often, I can learn something new about the development, writing and production of TV series that I didn’t know before despite my own experience in the biz. Here are some short reviews of three recent releases.